This article was originally published by the Herald-Dispatch.

CHARLESTON — A Charleston courtroom morphed into a chemistry class Tuesday as a witness in a landmark opioid crisis trial broke down opioids to their molecules and explained how opioid use disorder takes hold of drug users.

Dr. Corey Waller, a doctor who specializes in addiction medicine, said opioids work by activating opioid receptors within a nerve. He said when taking heroin, hydro- or oxycodone, dopamine levels in a body increase 2,150%, which permanently harms the body and leads to substance use disorder and disruptive behavior that comes with it.

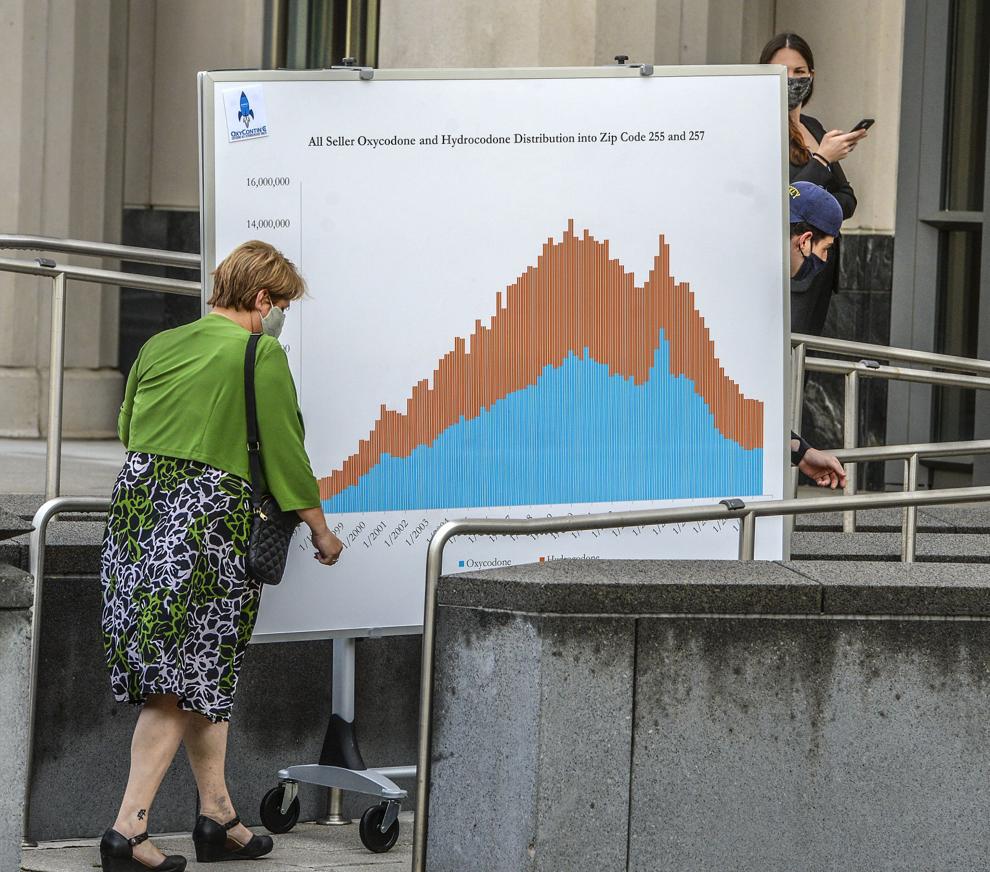

The trial is the result of a civil lawsuit filed by Huntington and Cabell County in 2017 accusing three opioid distributors of fueling the opioid crisis in the area after shipping more than 80 million opioid pills to the area over an eight-year period.

The “Big Three” defendants — AmerisourceBergen Drug Co., Cardinal Health Inc. and McKesson Corp. — defended themselves Tuesday by pointing at flaws in their relationship with the Drug Enforcement Administration, arguing they did not set supply quotas or prescribe the pills and once the pills were delivered, they were out of their control. Beyond that, they had no control or involvement with illicit street drugs, which are the current cause of the crisis.

The governments argue heroin, which has nearly the same chemical makeup as oxy- and hydrocodone, is cheaper and was easier to access when the number of pills distributors sent to the area dramatically decreased about 10 years ago.

The governments want paid for costs associated with past and future efforts to eliminate the hazard, arguing the wholesalers failed to follow a duty under federal law to monitor, detect, investigate, refuse and report suspicious orders of prescription opiates in the county.

The case is the first to go to trial among hundreds alleging the same. It’s a bench trial, which means the outcome will be decided by Charleston-based U.S. District Judge David A. Faber.

While being questioned by Cabell County attorney Paul T. Farrell Jr., Waller said the body produces its own natural opiates, like endorphins, within opioid receptors in a nerve. When endorphins bind to receptors, dopamine — known as the pleasure hormone — is released.

When unnatural opioids enter the body, they attach to those receptors tighter than endorphins.

Natural opioid medicines, like morphine and codeine, are extracted from poppy plants or other sources. Semi-synthetic opioids — oxycodone or hydrocodone — also derive from the poppy plant, but are lab enhanced. Synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, are completely lab created.

The molecular structure of semi-synthetic opioids are nowhere near the naturally produced endorphin structure, Waller said, and heroin, oxycodone and hydrocodone all have the same core molecule.

Waller compared the body’s natural opiate system to a soundboard with dozens of knobs and buttons, in which you are in full control and can make subtle changes to find the perfect sound. Ultimately all you have to do is turn it off and you will see no effects.

On the flip side, opioid medicine introduced to the system is like a volume button. There is no subtlety or control, just an up or down knob, which can often be like an explosion that leaves damage, Waller said. Fentanyl turns the receptor up about as high as you can get, he said.

Waller said the center of substance use disorder is dopamine, a naturally occurring hormone in humans that creates happiness and motivation. When disrupted, the brain and body fail.

Dopamine levels on a normal day would be about 50 nanograms per deciliter and on a bad day would drop to 40, making it difficult for someone to be motivated. On a great day, it could be around 100. The higher the level, the more invincible a person feels, including a lessened sense of pain or fear.

“When we disrupt that part of the brain, we really disrupt all aspects of … how we react,” he said.

After the first use, Waller said, the body is going to not want to make you go that high anymore, which causes a higher tolerance and causes the user to need more to feel that level again.

“The brain doesn’t like to be told what to do, so it begins to regulate the system,” he said.

The body will shrink the amount of natural dopamine levels from the confusion of non-natural opioids being introduced to the body. The effect leaves dopamine levels well below a human’s worst day. As a result, users are often left chasing that high and happiness for years.

Waller said he wouldn’t define prescription drugs as a gateway drug, because they have the same effect on the receptors. The body cannot tell the difference.

“No, it has no idea,” he said. “The brain doesn’t know what drug you just gave it. It just knows what reaction it had.”

Alcohol has less impact than opioids and is more predictable, but can still be harmful, he said.

At the questioning of Jennifer Wicht, an attorney for Cardinal Health, Waller said things like genetics and adverse childhood experiences play a role in whether or not a person is going to have opioid use disorder. Wicht said studies show as much as 50% of people are at risk of addiction.

Wicht said hydro- and oxycodone are legally prescribed drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration and highly regulated. Defendants argued it was not their duty to control the amount of pills. The DEA, West Virginia Board of Medicine and others pushed for higher pills and they filled the orders, they said.

When asked if he thought there were patients with legitimate need for hydro- and oxycodone, Waller said yes, at the lowest possible dose for a short amount of time. If they need it for more than a week, they would need to be under supervision, in his opinion.

Nonetheless, Wicht said the wholesaler does not collaborate with doctors in writing the prescriptions and doesn’t have any interaction with the patients. The government is who controls the amount of pills distributed.

The sides picked apart several publications, pointing to the bits that supported their stance.

Timothy Hester, an attorney for McKesson, referenced several articles, newsletters and more dating as far back as the 1980s that said no patient should have to endure intense pain and encouraged higher distribution of opioids.

At the questioning of Farrell, Waller said the shift in more prescribing of opioids dates back to the 1980s and it was decades before opioid distribution skyrocketed.

Hester also pointed to several writings, which said the current drug issue is caused by illegal or fake opioid pills or drugs being shipped to the Mountain State by illegal dealers. Waller said it would be hard to tell counterfeit pills from a legitimate one and the former could be deadly.

The trial is expected to continue Wednesday with testimony from former West Virginia health commissioner Rahul Gutpa.