This article was originally published by the Herald-Dispatch.

CHARLESTON — Drug wholesalers accused of fueling the opioid epidemic by shipping millions of opiates to Cabell County over a nine-year period continued to blame federal regulators in court Tuesday and attempted to discredit years of work completed by a data analyst.

The city of Huntington and Cabell County argued that the defendants — AmerisourceBergen Drug Co., Cardinal Health Inc. and McKesson Corp. — became culpable when 127.9 million opiate doses were sent to the county from 2006-14. When the number of shipped doses decreased around 2012, users were made to turn to illicit opiate drugs, like heroin, they said.

The defendants said they did report suspicious orders to the Drug Enforcement Administration, but never heard back and were unsure of the next step to take because of lack of communication. They attribute the volume to DEA pill quotas and a rise in prescriptions written by doctors for a population with myriad health issues.

Craig McCann, a data analyst, said Monday the pill shipments were not a complex issue. Nearly 90% of the doses were sent to the county by three distribution facilities owned by the defendants and half of the opiate supply landed at nine pharmacies out of more than 40 in the county.

Plaintiffs argued that when the defense reduced the number of pills shipped around 2012, it made users turn to illicit opiate drugs, like heroin.

Cabell County Commissioner Jim Morgan, accompanied by state senator and Cabell attorney Mike Woelfel, said sitting through Tuesday morning’s testimony and seeing charts from the data made the defendants’ guilt obvious to him.

It’s been years since the lawsuit was first filed, and Morgan said he was glad Cabell County residents finally have their time in court.

“You sort of think, ‘Ah. Well. Let’s see what happens.’ Now we are actually here. I think it’s very interesting, and I’m very hopeful,” he said. “I think what all of us really hope comes from it is a way of addressing the problem and preventing it in the future.”

McCann’s testimony continued Tuesday with him comparing what opiate shipments single pharmacies received compared to the top four stores of three pharmacy families (Fruth, CVS and Rite Aid).

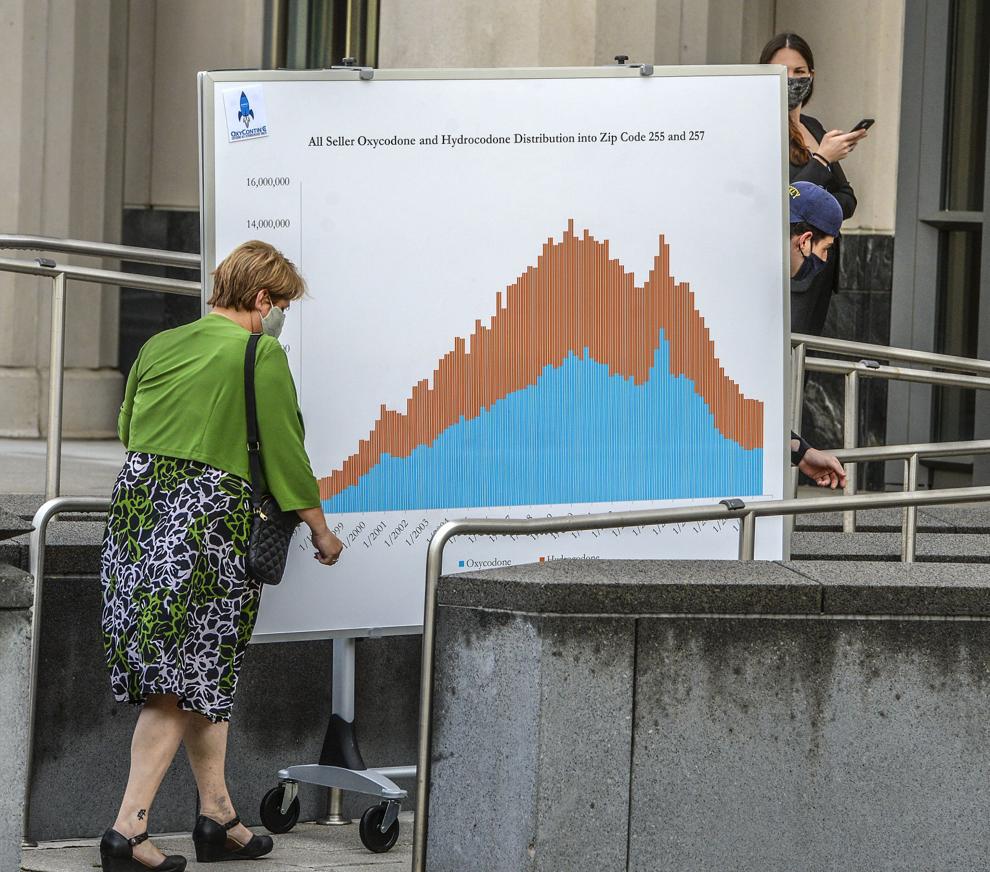

Charts showed the pharmacies were receiving opiates at a rate disproportionate to that of the United States average and the single pharmacies were receiving the drugs at a rate even higher. As time went on, more powerful opioids were being distributed in Cabell County, McCann said.

To make the comparison, McCann used MME — morphine milligram equivalent, a tool used by doctors to compare different drugs as a simplified, unified measurement. A dose of oxycodone has a potency about 1.5 times that of morphine, for example, and MME places them on the same level.

Joe Mahady, an attorney for AmerisourceBergen, said McCann was not an expert on medical needs for opiates, nor was he a doctor who could say how many prescriptions should have come out of the county. MME is not in ARCOS DEA pill data, and Mahady said it was based on McCann’s own calculations based on an equation he got from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.

McCann said the ARCOS data shows four Fruth Pharmacies in Cabell County together received 14.8 million hydro- and oxycodone dosage units, or 116 million MME over the nine years, with AmerisourceBergen and Cardinal Health accounting for about 98% of the supply.

Four Rite Aid stores in Cabell received 8.8 million dosage units and 72.4 million MME. While Rite Aid, which also owns a distribution center, sent 63% of hydro- and oxycodone doses, McKesson sent 64% of the MME, meaning by strength, McKesson sent larger, stronger amounts of opiates.

Four CVS stores received 124.7 million MME, 67% of which came from Cardinal Health.

Family Discount Pharmacy, a single pharmacy in Mingo County, received 15 million hydro- and oxycodone dosage units, or 121 million MME. Hurley Drug Co. pharmacy in Williamson, West Virginia, received 9.8 million dosage units during that time and 64.4 million MME.

Senior U.S. District Court Judge David A. Faber, who will ultimately decide the case, asked why pharmacies so far away from Cabell County were relevant. The plaintiff attorney said it would be tied together over the next few weeks of trial.

Paul Schmidt, with McKesson, and Mahady said the plaintiffs were fluffing numbers, choosing the highest ones to make their case and manipulating graphs to different scales to make them look more impressive.

Mahady said at least one chart listing data from the 1990s to 2010s, which shows 255 and 275 ZIP codes, is inaccurate because it covers a broader geographic area than just Cabell County and includes all distributors, not just the “Big Three” on trial.

The distributors said they had been asking the DEA for access to ARCOS (Automated Reports and Consolidated Ordering System) data for over a decade, but they would not do so. Schmidt said it wasn’t until 2018 that the DEA made it so they could see other distributors’ data for the previous six months.

Mahady called McCann unreliable, pointing to a federal court ruling in which a judge said McCann “actively” and “knowingly” misrepresented his data while being paid during arbitration in a separate court case. The finding was reversed by a higher court, but Mahady said that did not mean his testimony was correct.

Mahady pointed to McCann’s testimony Monday, during which he used three datasets to determine if the ARCOS data was accurate. What was reported to the DEA from AmerisourceBergen lined up 99.9%, he said.

“What that means is everything AmerisourceBergen shipped into Cabell County and the city of Huntington from 2006 to 2014 was reported to its federal regulator, the (DEA), right? They had it all,” he said.

Mahady then said the analyst’s report accounted for just 88.43% of the full ARCOS data — such as sales or transfers of pills. It did not account for .58% returned, or number of destroyed pills, about 3.84%, and more.

In an attempt to poke holes in his analysis, Mahady pointed to another of McCann’s charts that said AmerisourceBergen shipped pills to McCloud Family Pharmacy in Lavalette, West Virginia. It said 57,720 doses of hydrocodone were sent in October 2011.

He pointed to AmerisourceBergen transactions in which more than 15,000 pills were shipped back to the wholesaler from the pharmacy in October and November 2011.

McCann said data left out accounted for a minuscule amount of the pills and he felt his analysis was still accurate.

The local VA hospital accounts for about 21% of its hydro- and oxycodone shipments McKesson made, it said. After removal, it leaves them accounting for just 6% of the total distributor market, Schmidt said.

Schmidt said the numbers McCann used to make his per capita findings were unreliable because the U.S. census numbers were partially reached mathematically because Huntington has a population that is hard to count.

Mahady said Cabell County is a hospital hub for the Tri-State. Cabell Huntington Hospital serves more than 29 counties in the area and 360,000 people, who could come to Cabell County for their appointments and have their prescriptions filled in the county as well.